A fellow poet and long-time student of mine gifted me the use of her family’s cottage on Cape Cod. Through screen-windows and from chairs perched on the edge of a hill, I’ve passed the last week watching the tide come in an out, and the ocean beyond that. The sounds and scents of sand, pine, sea roses and rain have replaced the sounds of village life for now.

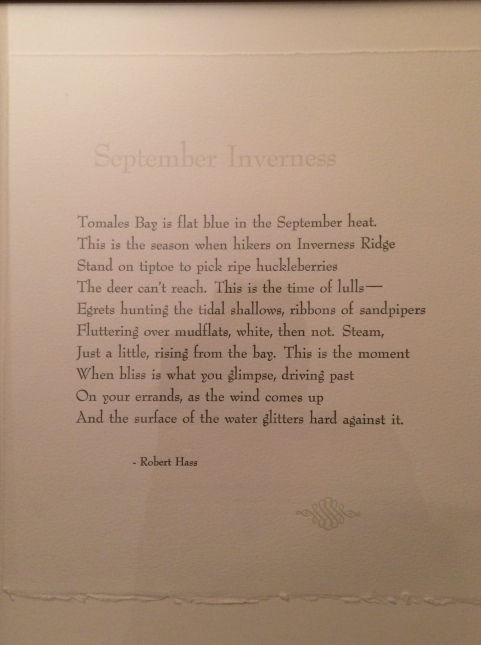

There’s a passage in the prose poem, “On Looking at the Sea,” by Thomas A. Clark that goes “As bladder wrack will float a stone, contemplation of the horizon brings a perceptible lifting of the center of gravity.”

I feel that. As quiet as my at-home life actually is, the pace of looking and perception, the sustained consideration that’s possible while away from regular life, makes possible a very different experience of the world, and of my self.

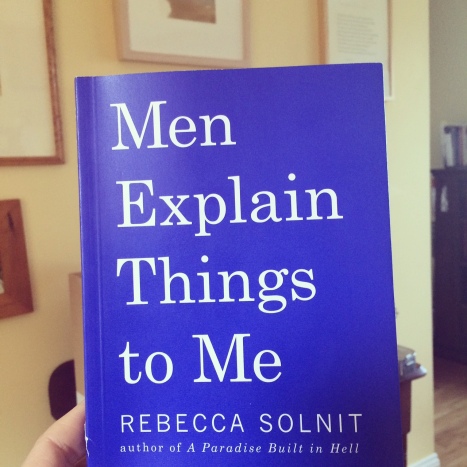

I’ve spent some time looking at paintings by Agnes Martin this week, too, after a reader suggested that the poems in my book, Pilgrim, called to mind a similar quality of quiet and stillness. See some of Martin’s work here.

“We have been very strenuously conditioned against solitude. To be alone is considered to be a grievous and dangerous condition.” Agnes Martin

I think that’s true for a lot of people, though not for me, probably because I grew up in the woods and spent a great deal of my youth alone, looking at the world from up high in climbing trees, or playing in meadows and in streams, if not alone, then with other kids who didn’t have televisions or electronic toys, and who were sent outside to explore and to be with ourselves.

I think that’s true for a lot of people, though not for me, probably because I grew up in the woods and spent a great deal of my youth alone, looking at the world from up high in climbing trees, or playing in meadows and in streams, if not alone, then with other kids who didn’t have televisions or electronic toys, and who were sent outside to explore and to be with ourselves.

I’ve also reread Anne Truitt’s Daybook: Journal of an Artist, written between the years 1973-1979, in which she documents her process and about sculpture. I was a small child during the years she said the following, about the difference between herself and her student’s sensitivity to sound:

“I wonder if my student’s senses are not actually different from mine. I overload so much faster than they do. Could it be that my baseline of stimulation at birth in 1921 in a small country town renders me incapable of adjusting easily to a range of visual and aural impact fifty-eight years later? The curve of environmental stimulation from 1921 to 1979 is steep, right straight up. Recalling my childhood, I hear birds, leaves in wind, human voices, the crumple of paper, the fall of beans in a barrel, barks, miaows, and occasionally horse’s hooves clip-clopping. That is not much sound to take in. Most of my students began to live around 1960. Muzak already filled public buildings, and what is to me, the painful rasp of the mechanical television voice threaded the daily life of householders. To compound this aural repletion with the visual, add televised images.”

I think about these things all the time. Do you? Do you think about what meets your eyes each day, and what fills your ears, and how that shapes your experience day to day?

As I began to transcribe the above passage, for the first time in over a week, the sound of a lawnmower started up somewhere in the neighborhood. A work truck beeped as it backed up and someone turned on a leaf blower. In contrast to other places in America, this is not the usual background sound in Sladeville, the former artist colony where I’m staying, probably because the sandy soil makes the cultivation of the Quintessential American Lawn a fruitless labor and foolish exercise. As a result, the landscape is left a little bit wilder, and the soundscape remains wilder too, if not just now, suffused with birdsong and wind sounds instead.

I grew up with painters for parents and these days I co-teach “Small Pages” workshops with my mother, Carol C. Spaulding, inside and outside her studio/gallery near Glen Lake, Michigan. In these day-long intensives we explore artistic practice as contemplative practice. Our next session happens on Saturday, August 20th, and offers a day of working with painted collage and writing prompts to help foster calm and creativity, and perhaps relieve you from concerns related to audience and commerce. You can find out more on my website. Or just reply to this email and I’ll add you to the class. Our limit is 8—no experience necessary. We’ll surround you with a burgeoning summer garden, trees, flowers galore, and birdsong. We’ll also provide all the materials necessary for the course, and send you home with a custom artist’s kit.

If that date doesn’t work for you, consider joining me in the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore for a three-hour nature-writing and poetry workshop on August 18th. Enroll via Glen Arbor Art Association at 231-334-6112. Finally, this Thursday, my mom will also host a workshop to help you loosen up your mind, make some marks, and devote yourself to the joyfulness of “Messing Around With Paint.” All of these experiences are intended to cultivate a quality of presence that you can carry with you into your art—or into the world. No prior experience necessary.

Agnes Martin again: “Art work comes straight through a free mind—an open mind. Absolute freedom is possible. We gradually give up things that disturb us and cover our mind. And with each relinquishment, we feel better.”

All photos of the same view: Pamet River at Truro, Cape Cod. Late July 2016.